Once upon a time, the French tried to change time. Or rather how we tell time. You might think it was at a time when people thought the world was flat, but it was actually to embrace logic and coherence that the change was made.

It was 4 years after the 1789 revolution, when the French Revolutionary Calendar was introduced in 1793, and it was meant to be the dawn of a new beginning.

Also known as the French Republican calendar, the idea was to do away with the old ways and usher in a new era of science and thinking. No more January, February, March, or Sunday, Monday, Tuesday, the new French Revolutionary calendar would have 12 months a year starting in autumn. It would also have:

- 3 weeks in a month,

- 10 days in a week,

- 10 hours in a day,

- 100 minutes in an hour,

- 100 seconds in a minute

At the time, humans had already accepted that the earth was round, that it went around the sun and more. And yet France said au revoir to the usual Gregorian calendar that we know and love today, and heralded the start of this new “rational” calendar.

It sounded logical enough, until it all went quite wrong. So let’s explore what happened, shall we? Allons-y!

The Origins

Even today, If you have a French name, you have a Saint’s name day in the French calendar. The calendar is based on the Catholic saints, and older French people will note when is the Saint’s day of their family members and remember to wish them.

The Calendar of Saints goes back to the days when Christianity first came to Europe, and the Catholic Church was attempting to convert the locals to the new religion. Early Christian custom consisted of commemorating each martyr annually on the date of their death, along with All Saints’ day celebrated on November 1st.

After the Revolution, a group of revolutionaries had the idea to do away with this old system that they saw as supporting the monarchy, and create a more secular calendar. The Catholic Church and its saints were all replaced. Christmas day did not survive either, it was replaced with Isaac Newton’s birthday.

Details of the New Calendar

In 1793, the French revolutionaries decided to introduce a calendar which still had 12 months, but each month would be made up of a fixed 30 days. The 30 days would be divided into 3 weeks of 10 days each, instead of 4 weeks of 7 days, to make the whole thing even. The first day of the year would be the Autumn Equinox, when the 12 hours of day and night are equal.

a) Months of the year

Each of the 12 months of the year was renamed to celebrate nature. Mother Earth was to be featured front and center, with the months named after various flora, fauna, and the weather:

| Month | Origin | Starts on |

|---|---|---|

| Autumn | ||

| Vendémiaire | from French vendange, derived from Latin vindemia, “grape harvest” | 22, 23, or 24 September |

| Brumaire | from French brume, “mist” | 22, 23, or 24 October |

| Frimaire | From French frimas, “frost” | 21, 22, or 23 November |

| Winter | ||

| Nivôse | from Latin nivosus, “snowy” | 21, 22, or 23 December |

| Pluviôse | from French pluvieux, derived from Latin pluvius, “rainy” | 20, 21, or 22 January |

| Ventôse | from French venteux, derived from Latin ventosus, “windy” | 19, 20, or 21 February |

| Spring | ||

| Germinal | from French germination | 20 or 21 March |

| Floréal | from French fleur, derived from Latin flos, “flower” | 20 or 21 April |

| Prairial | from French prairie, “meadow” | 20 or 21 May |

| Summer | ||

| Messidor | from Latin messis, “harvest” | 19 or 20 June |

| Thermidor | from Greek thermon, “summer heat” | 19 or 20 July |

| Fructidor | from Latin fructus, “fruit” | 18 or 19 August |

b) Days of the Week

The new “week” of 10 days was called a décade, instead of the french word for “week” (semaine). And instead of the usual monday (lundi), mardi (tuesday), wednesday (mercredi), the days of the week changed names as well:

| Day | Meaning |

|---|---|

| primidi | first day |

| duodi | second day |

| tridi | third day |

| quartidi | fourth day |

| quintidi | fifth day |

| sextidi | sixth day |

| septidi | seventh day |

| octidi | eighth day |

| nonidi | ninth day |

| décadi | tenth day |

c) Hours of the Day

In addition, each day in the new French Revolutionary Calendar was divided into 10 hours, each hour into 100 minutes, and each decimal minute into 100 seconds.

This made an hour consist of 144 minutes (more than twice as long as a 60-minute hour), a minute was 86.4 seconds (instead of 60 seconds), and a republican calendar second was 0.864 of a normal second.

New clocks were manufactured to display this decimal time, even though but clockmakers all over France complained.

Gregorian Calendar vs French Revolutionary Calendar

Pope Gregory XIII and the Catholic church may have come up with the Gregorian calendar that we use today, but it does have a scientific basis. The calendar establishes a year as the time it takes for the earth to revolve around the sun. In practical terms, that is 365.2425 days, or rather 365 days + 1 day every leap year.

So while it sounded logical for the French to have 10 days per week, and 3 weeks per month for 12 months, that only gave the Revolutionaries 360 days.

That was not enough for the earth to revolve around the sun. To compensate, 5 extra days were added to the end of every year, with an additional 6th day every leap year:

| Name | Explanation | Date |

|---|---|---|

| La Fête de la Vertu | Celebration of Virtue | on 17 or 18 September |

| La Fête du Génie | Celebration of Talent | on 18 or 19 September |

| La Fête du Travail | Celebration of Labour | on 19 or 20 September |

| La Fête de l’Opinion | Celebration of Convictions | on 20 or 21 September |

| La Fête des Récompenses | Celebration of Honors (Awards) | on 21 or 22 September |

| La Fête de la Révolution | Celebration of the Revolution | on 22 or 23 September (on leap years only) |

The additional days were to celebrate the Revolutionaries themselves. The holidays were called the Sansculottides after the Sans Culottes, which was the name of the revolutionaries gave themselves.

Sans Culottes means “without underwear”, which is to represent the ordinary man, as opposed to noblemen who did have the luxury of wearing underwear.

With these new additional days, it now seemed like the new French republican calendar would be in line with the earth’s planetary cycles as well as being logical.

The Problems

But from the start, there were problems. The Revolutionaries found that it not so easy to change people’s habits, especially considering that many people could now read and write.

- The ordinary French worker now needed to work 9 days before having 1 day off, instead of 6 under the old system.

- The New year (the Autumn Equinox) is based on solar cycles, so the new year fell on a different date every year.

- French people were used to going to church on Sundays, and now the new schedule (purposely) threw that off.

- French people had to wait a full year to get 5 days off in a row.

- For harvests in the fall, such as the grapes for wine, it was not good timing to give everyone 5 days off.

- The calendar was confusing, especially since France had several colonies at the time.

- France had trade links and borders with the rest of Europe and North America who were following the Gregorian calendar.

- The new clocks were confusing, and this part of the project only lasted for 17 months.

Duration and Abolition

By the time Napoleon Bonaparte became First Consul of France in 1799, the French Revolutionary Calendar had already been in effect for 6 years.

Since he had a habit of going around conquering his European neighbors, the new calendar was exported to other countries under French rule, including parts of Belgium, Netherlands, Germany, Switzerland, and Italy.

But Napoleon had bigger fish to fry than to convince local populations (including the French themselves) that the French Republican calendar was a fabulous idea. By this time, many of the Revolutionaries who had thought up the calendar had themselves met the guillotine.

Napoleon Bonaparte abolished the calendar on 9 September 1805, with a Décret Impérial. The Revolutionary calendar had lasted 13 years, with the Gregorian calendar beginning again on 1 January 1806.

So what do you think? Do you think the French Republican Calendar would have caught on if it had more time? If you enjoyed that article head over to the actual French calendar of holidays, with all its quirky celebrations. A bientôt!

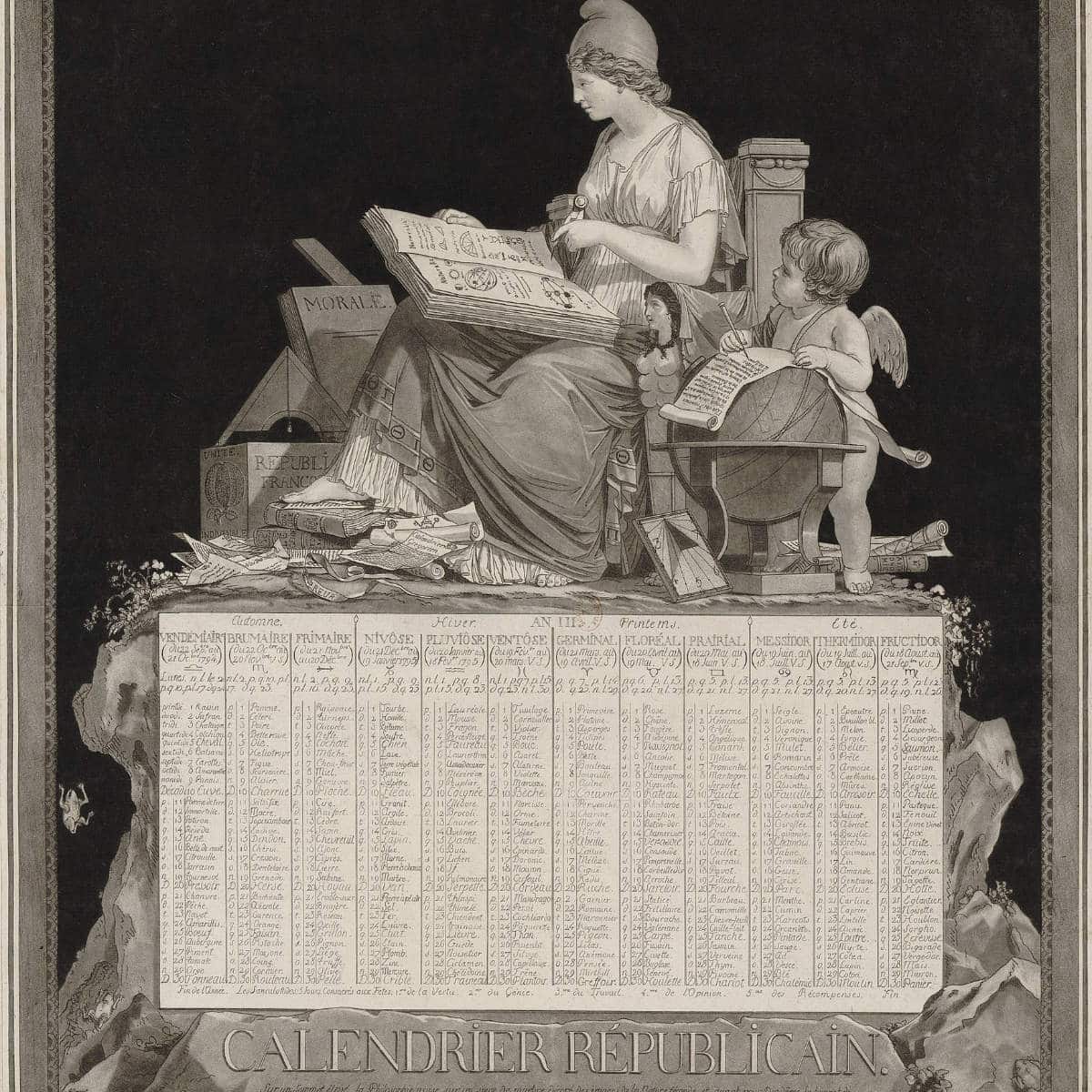

¹ Featured Image: Debucourt Image courtesy of Wikipedia Commons