In Paris, there is a certain type of architecture that is so famous and popular, it just goes by one name: the Hausmmanien. It is named for a French architect born in Paris by the name of Baron Haussmann, who had a very strong aesthetic and a free hand to do as he wanted.

He was chosen by Emperor Napoleon III to transform the French capital, and would do so in a span of merely 17 years, between 1853 to 1870.

With beautiful mouldings, tall ceilings, and elongated windows, the charm of this 19th-century Parisian architecture is undeniable. And when you imagine all the history, events, and personalities that these walls have witnessed, well this is what makes romantic Paris the city that it is today.

So let’s find out more about the buildings and architecture in Paris, shall we? Allons-y!

- 1. Demolishing a medieval city

- 2. Inspired by London

- 3. Napoleon III and Baron Haussman

- 4. Hausmann-style facade

- 5. Height of the Building

- 6. High ceilings and mouldings

- 7. Ground floor shops and commerce

- 8. First floor Mezzanine

- 9. The Aristocratic Noble second floor

- 10. Third and Fourth floor with minimal decorations

- 11. Fifth floor long balcony

- 12. Chambres de bonnes (servants quarters)

- 13. Basement cave

- 14. Old pipes, bad insulation and metal braces

- 15. Retrofitting elevators

- 16. No Parking

- 17. Large boulevards

- 18. Roundabouts

- 19. Surrounding parks

- 20. Other changes by Haussmann

- 21. Art Nouveau and Art Deco buildings

- 22. 1970s buildings

- 23. New construction in Paris

1. Demolishing a medieval city

When Napoleon Bonaparte’s nephew Napoleon III came to power in 1848, Paris was unsafe and overcrowded. It was also a much smaller city in geography than what we see today.

Paris had a population of about one million people at the time, most of whom lived in crowded and unhealthy conditions. With narrow medieval buildings, there was no running water and sewage being dumped into the Seine. The city was in a midst of a cholera epidemic.

Having declared himself Emperor in the footsteps of his uncle, Emperor Napoleon III set about to put his mark on the city of Paris.

2. Inspired by London

Napoleon III had spent some time in London during a trip there and so was greatly inspired by how that city was laid out. The Great fire of London in 1666 had already wiped out much of the medieval city, and the legendary architect Christopher Wren had already reimagined much of the city.

By Napoleon III’s time, the Victorian era was in full bloom and prosperous London was miles ahead. Napoleon III wanted a Paris that would rival London and the country that had defeated and imprisoned his uncle.

3. Napoleon III and Baron Haussman

Napoleon III hired a French architect, Baron Haussman, to knock down the medieval neighborhoods of Paris and completely rethink how the country’s capital was laid out.

As Hausmann drew up his plans, thousands of properties across the city were expropriated by the French State in exchange for money. The State would recover the funds by reselling the new land in the form of separate lots to developers who had to build new buildings in accordance with Hausmann’s specifications.

The biggest problem was bringing fresh water to the city. He had a new aqueduct built to bring clean water from rivers in the Loire to a new huge reservoir near the future Parc Montsouris.

His efforts would increase the water supply of Paris from 87,000 to 400,000 cubic metres of water a day.

In addition, hundreds of miles of pipes were laid to distribute the water throughout Paris, connecting the new buildings to running water. A system was also created to use the less-pure water from the Ourq and the Seine, to wash the streets and water the new park and gardens.

Sewers were installed in Paris, and miles of pipes to distribute gas for thousands of new streetlights along the Paris streets. This is why Paris became known as the City of Lights.

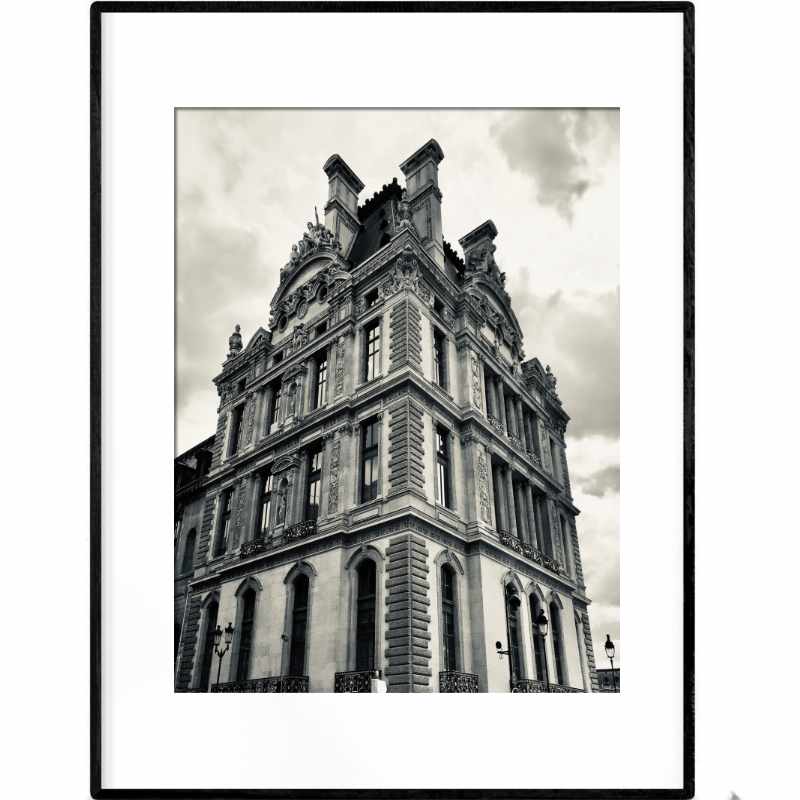

4. Hausmann-style facade

This style of architecture became known as the Haussmannian, and there is a very specific look to it.

Haussman required the buildings to be the same height and in a similar style, and to be faced with cream-coloured stone, creating a uniform look.

Famous French writer Victor Hugo wrote at the time that it was hardly possible to distinguish what the house in front of you was for because it all looked so similar.

Initially Parisians hated it, as old and poor neighborhoods all over Paris were destroyed to make way for the new Hausmmanien style that catered to the rich bourgeoisie. In a span of 17 years, Haussmann would completely rebuild the city of Paris.

5. Height of the Building

Hausmann’s new buildings would contained apartments spread out over the five or six floors depending on the width of the road. Buildings were allowed to vary from 12 to 20 metres in height.

Even today, French regulations require that residential buildings in Paris cannot be higher than 50m, while commercial buildings no higher than 180m.

6. High ceilings and mouldings

Despite the height restrictions of the buildings overall, the interiors of the buildings were known for their high ceilings and elaborate mouldings on the walls and ceilings.

Parisian architecture is known for its high ceilings, borrowing from the luxurious feel that palaces like the Château de Versailles had made so popular. This however does cost money, since the building has to be taller to accommodate the additional ceiling height on each floor.

The standard apartment ceiling height for new construction in Paris is 2.5 meters, while these older Haussmann buildings have around 3 meters in height. The height however depends on what floor of the Haussmanian, you are on, as each floor targeted a particular socio-economic class of residents, and the ceiling height was an indicator of wealth.

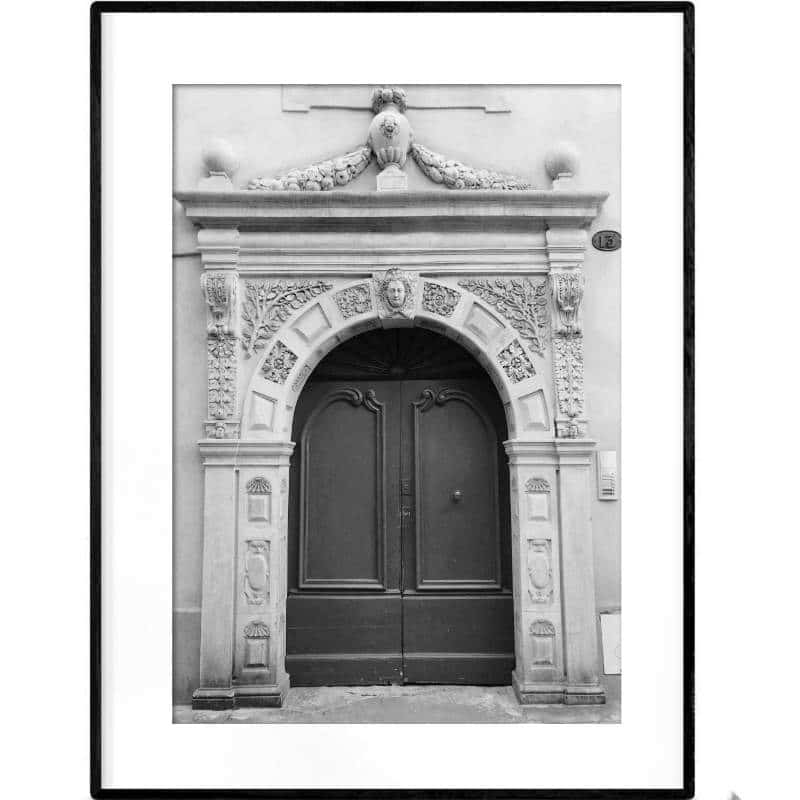

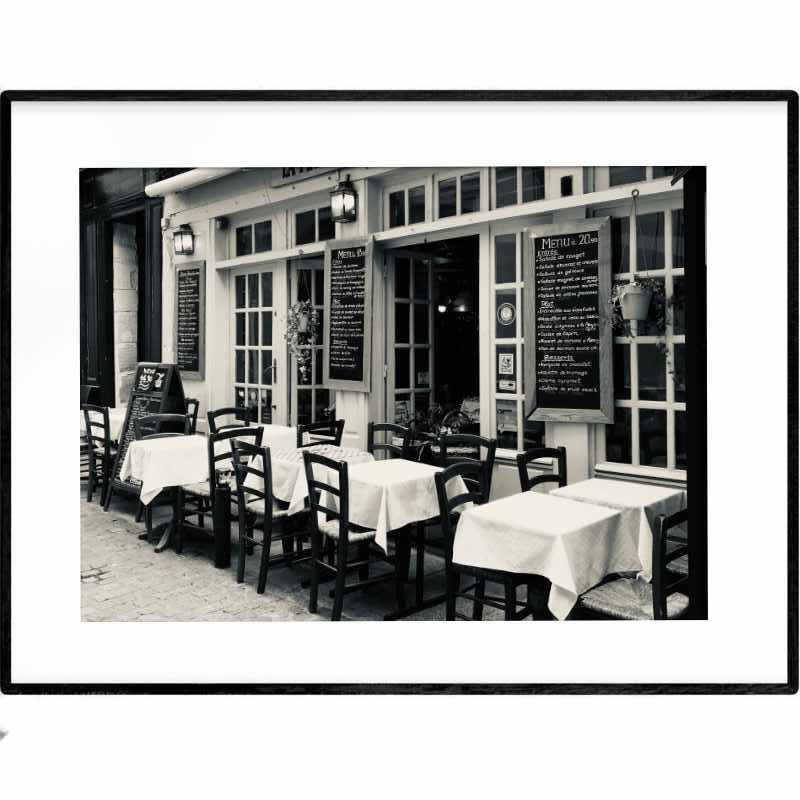

7. Ground floor shops and commerce

The ground floor was reserved for shops, restaurants, and other commerce. Since Haussmann wanted a uniform look, there shop owners were only allowed to modify small portions of their facade, in keeping with the original aesthetic.

8. First floor Mezzanine

First floor apartments were traditionally reserved for merchants to use for storage purposes, or to live in as the owner of the ground-level shops. As such, they do not have the same ceiling height as other storeys.

And since the entryway was usually a large enough door to accommodate a carriage, the windows of the 1st floor were lowered to preserve the symmetry of the building from the outside, while at the same time not wasting space on the “common folk”.

(Note: The first floor in France is the floor above the ground floor, which is what the North Americans refer to as the 2nd floor.)

9. The Aristocratic Noble second floor

The second floor was meant to attract nobility and rich aristocrats and so have the highest interior ceiling at 3.20 meters.

In addition, the 2nd floor required ornate ironwork for larger balconies and guardrails that extended across at least 2-3 windows. In addition, the window frames were also richly decorated with elaborate mouldings that would draw the attention of the eye.

These 2nd floor apartments were the most prestigious in Hausmmanien architecture because there were no elevators at the time. The nobility wished to be higher up, but did not want to tire out by climbing stairs all the way to the top. The 2nd floor was a good compromise.

10. Third and Fourth floor with minimal decorations

The 3rd and 4th floor apartments usually do not have the same ornate exterior or long balconies as the 2nd floor, just enough to make it visually interesting.

These apartments used to target the middle class, like civil servants and employees, compared to the aristocrats on the 2nd floor.

Inside, the ceilings on higher levels are incrementally lower, the higher you go in the building. (They are still higher than the current 2.5m standard, so these apartments still remain much sought after.)

11. Fifth floor long balcony

On the 5th floor, the Haussmannien building usually features a long balcony covering several windows. This was for aesthetic purposes, to give the building a distinguished look.

The 5th floor is rather high in a building without an elevator, so these apartments were not particularly sought after.

12. Chambres de bonnes (servants quarters)

On the top floor of the Hausmannian buildings are the chambres de bonnes. These tiny rooms were meant to be servants’ quarters and did not have individual kitchens or bathrooms.

Instead, servants would have access to one toilet and bathroom on the floor, which they would have to share.

Roofs were required to fit on a 45 degree diagonal, meaning that in addition to lower ceilings, these apartments not have proper headroom across the full space.

In addition, the Parisian roofs that the city is renowned and admired for, are made out of zinc, and so it gets incredibly hot on the top floors of the Hausmannian in the summer. (Even today air-conditioning is not the norm in Paris.)

These days, you will still find chambres de bonnes available for rent, assuming they meet the legal size of a rental, which is 9m2. Families in Paris will often have ownership of a chambre de bonne attached to their own apartment below, and keep them for a live-in nanny.

13. Basement cave

Because space is limited in Parisian apartments, most buildings also have what is called a “cave” in French which is actually a small room that functions as a storage locker.

They are not very large, perhaps 1-2 square meters and are usually in the dark somewhat damp basement of the buildings. In addition, Parisian buildings that are next to the quays of the Seine river are considered to be in a flood zone, so most residents know not to leave anything of value in their caves.

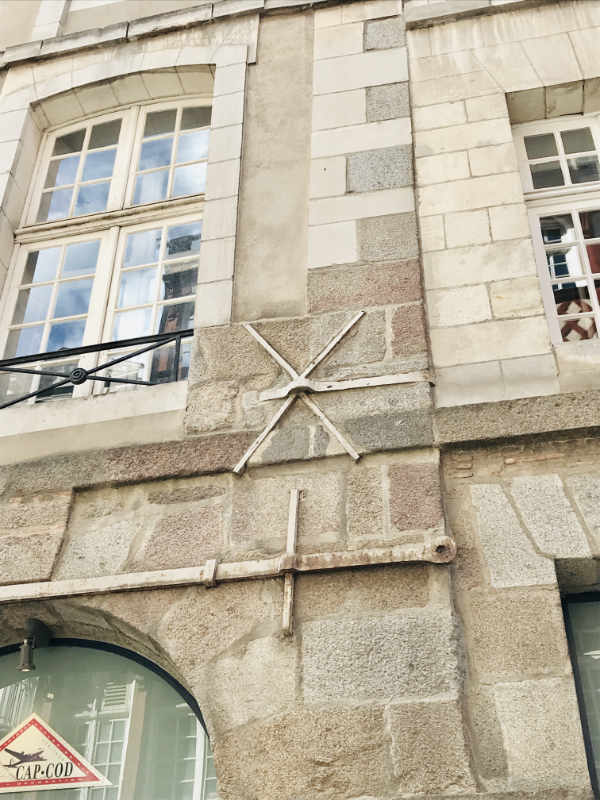

14. Old pipes, bad insulation and metal braces

Now, I don’t know if you noticed, but these beautiful 19th-century Hausmannien buildings were built in the 19th century. They are old. Ancient pipes leak like anything that is 250+ years old. Some buildings even have structural issues, and so have metal braces put in to keep them up.

Sound insulation is another problem. Haussmannien architecture did not include the same insulation that we build with today, and so complaints amongst neighbors are common.

☞ READ MORE: Household items you will own if you live in Paris

15. Retrofitting elevators

And as you can imagine with the old Parisian buildings, there were no elevators. These days, some building owners vote to have elevators retrofitted in, at huge costs.

This results in a lot of odd-shaped tiny elevators that will barely fit two adults. But residents can forget about trying to get in there with a wheelchair or a stroller.

In certain cases like the one below, the elevator looks big enough, but actually it is the doors that are too narrow for a stroller to get through.

16. No Parking

While elevators can be retrofitted, parking into an 19th-century building cannot.

As such, a majority of Parisians don’t have a car. A compromise they have made for having gorgeous tall ceilings, beautiful mouldings and classical fireplaces.

17. Large boulevards

Compared to the narrow streets of medieval Paris, Haussman’s idea was to have wide open boulevards lined with his new buildings. He liked straight lines to improve the flow of carriage traffic, and movement of goods and people.

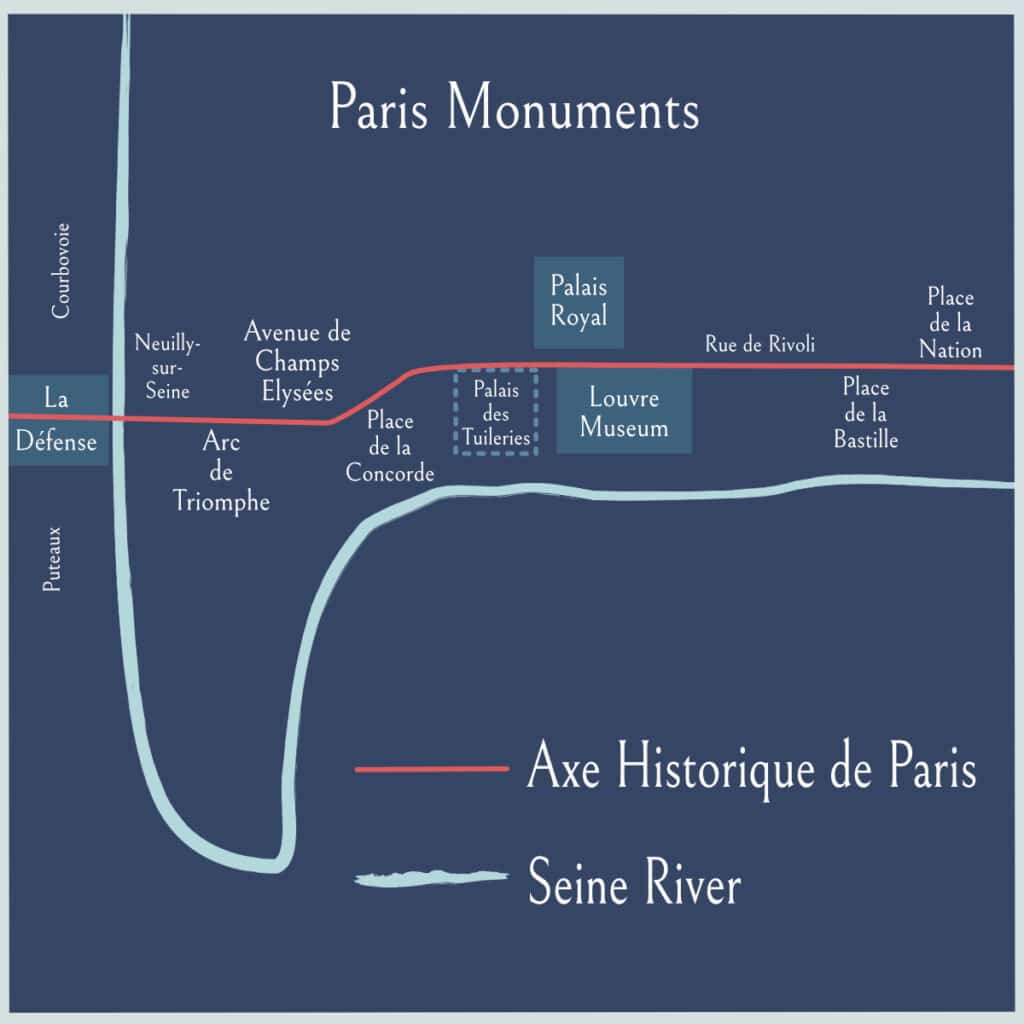

These large boulevards like the Champs Elysées and Rue de Rivoli were constructed, connecting the city from one end to the other with a network web of wide roads.

The main stretch of this road came to be known as the Axe Historique de Paris or Voie Triomphale (meaning “triumphal way”). It is perfectly straight, except for a slight bend in the road to follow the shape of the river Seine.

18. Roundabouts

In order to connect all these grand boulevards, large roundabouts were constructed to connect the streets in a star pattern.

The most famous of the Parisian roundabouts is of course the Place Charles de Gaulle Etoile with the Arc de Triomphe, which connects 12 different boulevards together.

19. Surrounding parks

Along with these rambling boulevards and beautiful architecture, Napoleon III also ordered the construction of four large new parks at each end of the city:

- Bois de Boulogne in the west in the 16th arrondissement

- Bois de Vincennes in the east in the 12th arrondissement

- Parc des Buttes-Chaumont in the north in the 19th arrondissement

- Parc Montsouris in the south in the 14th arrondissement

He also put in many smaller parks and squares around the city, so that no neighbourhood was more than a ten-minute walk from a park.

These days, Paris has some lovely parks sprinkled all around the city such as Jardin de Luxembourg, Parc Monceau, Jardin des Tuileries, etc. along with tiny garden squares where you least expect it.

20. Other changes by Haussmann

Along with new roads and buildings, Haussmann also had several of the bridges across the Seine rebuilt.

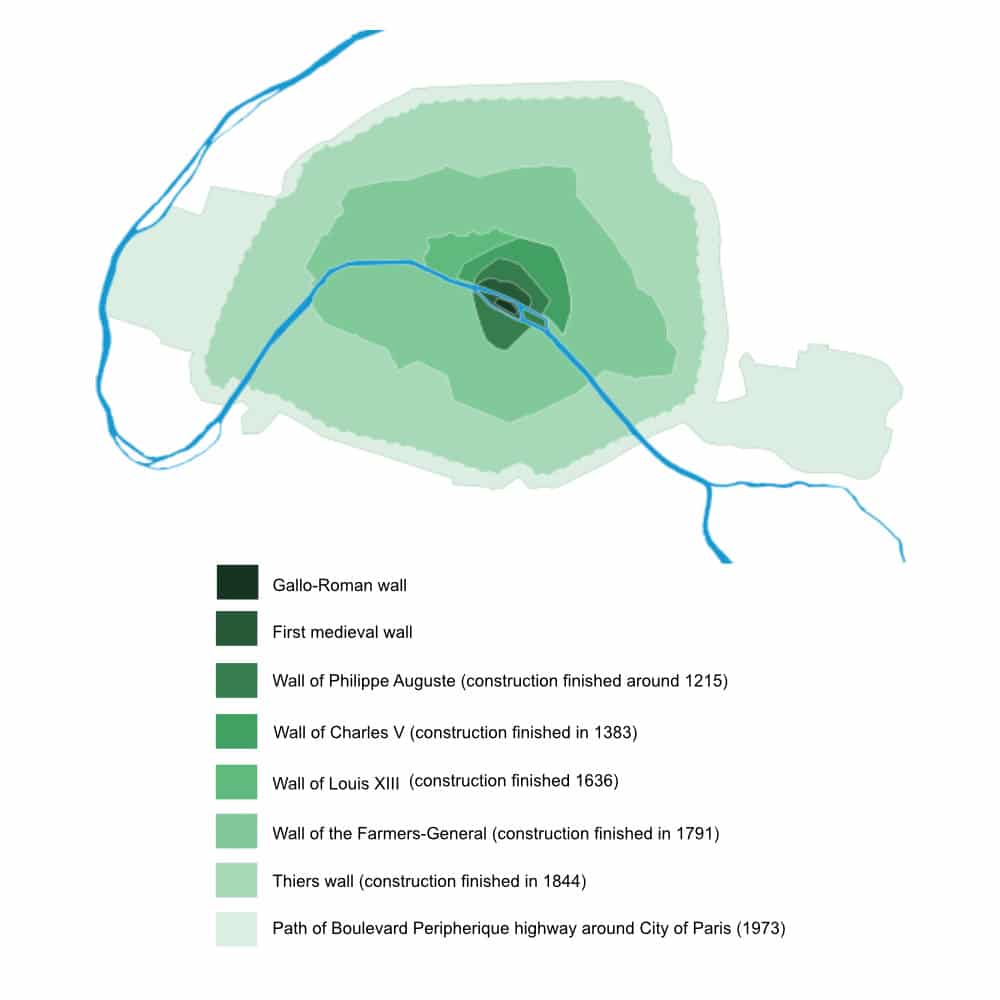

He also decided to extend the city of Paris to the fortifications of the Thiers.

Eleven municipalities bordering the old city of Paris were eliminated and absorbed into the city, including Belleville, La Villette, Passy, Batignolles-Monceau, Bercy, La Chapelle, Charonne, and Montmartre. Today you will recognize these names around Paris as metro stations.

Historians estimate that Baron Haussmann modified approximately 60% of Paris, including demolishing around 18,000 buildings, if not more.

By some estimates, this transformation cost more than 900 million gold francs in borrowings and also came at a huge social cost. It forced more than 25,000 inhabitants, almost all workers, to abandon the center of the city and to be pushed back towards the outskirts.

Against all this unrest, Emperor Napoleon III tried to shore up his support by declaring war on Prussia in 1870. He was swiftly defeated and spend his last years in England in exile. Haussman’s work would come to a halt.

21. Art Nouveau and Art Deco buildings

Baron Haussmann died in 1891 at the age of 81, and after him came a new type of Parisian architecture. In contrast to the rigid rules of the Hausmannien-style, the start of the 20th century led to a new type of Parisian building in the art nouveau and later art deco styles.

Keeping with the legal height restrictions, these new buildings broke the rules about mouldings and balconies, using more flare and creativity.

An example is the original La Samaritaine store that was built in 1905 and recently restored. Gone are the homogeneous facades, and each building stands out on its own.

22. 1970s buildings

After WWII, the reconstruction of France and the economy meant that new buildings no longer had high ceilings or fancy mouldings, both of which cost wasted space, time, and money. Instead, there rose a more modern construction, that could be Parisian or indeed anywhere.

However, if you are walking around the 13th arrondissement or around Montparnasse, you will notice that there are certain rather tall buildings with 20+ floors that seem to break all the previous rules. While these buildings would not stand out in any North American city, in Paris they stick out like a sore thumb.

This would be the 1970s. At the time, there was a serious shortage of housing in the city and the decision was made to lift the restriction on the height of Parisian architecture.

The problem arises in Paris because it is surrounded by a highway called the Boulevard Péripherique, which has enclosed the city with a wall, meaning that it can neither grow outwards nor up. And this is still the case today. The cost of living in Paris is more than 2-3 times the cost of living elsewhere in France.

All of which leads to that great experiment in the 1970s where tall buildings were allowed to be built, of rather questionable quality and aesthetics.

Today, local Parisians trying to buy an apartment tend to avoid buildings from the 70s, preferring any other era than that one.

Most of these buildings have been restricted to the outskirts of Paris and the 13th arrondissement, but the existing buildings remain only somewhat addressing the housing crisis.

23. New construction in Paris

New construction in Paris is relatively rare, since the preference is to rehabilitate existing buildings rather than build new ones.

On the odd occasion that an existing building is demolished and a new one built, the tendency in Paris is clear. The Hausmannien charm remains much sought after and so newer buildings tend to replicate that look, in a style sometimes referred to as faux-hausmannien. With high ceilings, built-in elevators, and (sometimes) parking.

If you enjoyed this article, you may enjoy reading more about living in Paris. A bientôt!